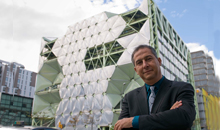

Enric Ruiz-Geli

Media-TIC has been dubbed the "Pedrera for the twenty-first century". Does your building represent a revolution in the language of architecture, as in the case of Gaudí?

Without a doubt. That comment was made by critic Daniel Giralt Miracle because he sees a similar attitude in the two projects. Gaudí created a new language for conversing with the city, based on the subject of housing. Now, in the digital age, the Media-TIC façade converses with the city, but our subject is energy. Gaudí worked with the craftsmen of his time, potters, glassmakers, carpenters, and we use the craftspeople of today, namely software programmers and energy engineers.

Another great element of Gaudí's work is nature. You defend an organic conception of architecture which emulates the internal processes of nature through the use of new technologies...

That's right. I enjoy recalling the words of Jorge Wagensberg. He says that if you look at nature, it's beautiful, but it is not in harmony. Nature is pure chaos, chance, indeterminacy and everything happens by some kind of magic. However, it's also true to say that nature performs. Look at photosynthesis. A tree is a factory that produces nourishment and medicine, it moves according to the wind, it looks for water in the water table, it's an energy-making machine and we, the architects of energy, look to nature not in the way that the Catalan Modernists did, inspired by its shapes and geometries, but by the scientific aspects of particles and physical movements.

Reading about Media-TIC, and even looking at it, you feel that humans had very little to do with its conception, which all originates from different variables in a computer...

Yes, it is true that we work with parametric designs that link to an AutoCAD plan and an Excel spreadsheet and as we draw it gives us real-time data about costs, natural light, the distance between staircases, etc. At Media-TIC, we have created a vertical communication that constitutes 8% of the ratio of the constructed building, whereas it accounts for 23% of the Torre Agbar. A low ratio means that we can free up a lot of square metres for people, for public use. However, it's also true that computers produce strange, barely human and non-symmetrical architectures that break with traditional forms.

Many would say that creating a sustainable building is more costly in the long-term than putting up a conventional one. Does Media-TIC contradict this belief?

Sustainability is a science in progress. The first phase belonged to the gurus: Al Gore and Jeremy Rifkin. Now we're in the second, radical phase, where sustainability establishes a dogma, a series of energy certificates, a technical code, the law, energy efficiency, etc. We still argue about who is sustainable and who's not. It's like feminism. You have to go through this radical phase, even though the current situation means we have to be radical. Look at Ferran Adrià. He's radical and he's revolutionised cuisine.

In what way?

This project had a budget of 1,300 euros per square metre. We did not want added sustainability costing 15%, which is a rather radical decision. We wanted to construct a building with a market value similar to the buildings around it to prove that the economy is no excuse. And this is what we've achieved with a public building, showing that you can build sustainable architecture and reduce CO2 emissions by 90%. We spent 50% of the budget on robots, computers and laser cutting.

A few weeks ago saw the premiere of How Much Does Your Building Weigh, Mr Foster?, a film about the career of Norman Foster. This question seems to be very symbolic for architects. The metal structure of Media-TIC has a 40% saving in terms of weight. Are you concerned about the lightness of your buildings?

Lightness is related to the lifecycle of buildings and their ecological footprint. If you save on weight, you save on foundations. Here, with a very high water table, creating a lighter foundation enabled us to save some two million Euros of cement, which will help us pay for the building's skin with ETFE. We save on materials, which we're not interested in, and we gain on "performance".

There are only four buildings in the world that has this type of extraordinary outer skin, a combination of plastic and glass called ETFE (ethylene tetrafluoroethylene), and you have created the first building in Spain to have this material. What's so special about it?

It's light, easy to use, saves on transport, doesn't burn, doesn't spread fire and is self-extinguishing. It's also high-performance and is a natural solar filter. With ETFE, which reduces air conditioning costs by 60%, we have created two patents.

Isn't there a contradiction in being committed to sustainability and building car parking spaces which encourage the use of private cars?

We are bound by the technical code of construction, which requires a certain number of parking spaces per square metre, which is extremely high. In fact, half the parking spaces will remain empty because the person-car ratio has, thankfully, dropped considerably.

Bearing in mind that architecture is a product of its context and surroundings, would you have constructed the same building at the northern end of Diagonal or on Gran Vía as you did at 22@, where there is an institutional commitment to establishing companies that make intensive use of new technologies?

Probably not, because, as they say, architecture is site-specific. We had to react to our context, starting by positioning the building at the same height as the social housing on our block so as not to compete with other nearby detached houses. We also wanted to leave the intersection open to create a public space where people can walk. We also installed a ramp for the buildings around us, so linking the entire block.

Do you feel that 22@ is following the script set down by its creators?

Generally speaking, yes. From an energy point of view, we have a new energy paradigm thanks to the Districlima network, which takes energy from the Besòs purification works and distributes it throughout the area. By linking up to the network, you're fulfilling the Kyoto Protocol with 25% clean energy. I can only think of two cases: Paris and Barcelona. I also believe that we have achieved a mix. We're surrounded by social housing. In London, social housing next to iconic buildings would be unthinkable. The same would be true in Paris. They function by ghettos and Barcelona breaks away from this. Social policies have been created to bring in big companies and make them live alongside universities, social housing and luxury homes.

And those who lament the passing of all the industrial heritage that has been lost along the way...

The Mediterranean city lives on an inheritance which is the old town, the Eixample district. We live with one model and now we're creating another. The co-existence of the two can be successful if we keep an open mind. We can experiment in this district and see the results. At the moment, I feel that it's working well. In any case, I'm a champion of intangible heritage. It's important to preserve the stones, but it's better to create the stones of knowledge and this building is one.

Press contact

-

Editorial department